In January 1826, Irving received a letter from Alexander Hill Everett, the American minister in Spain, with an offer to become an attaché to the American legation in Madrid. It carried with it no official duties, but Everett asked if Irving might be interested in translating a recently-published history of Christopher Columbus. Irving leapt at the opportunity—and the four years he would spend in Spain would be some of the most productive years of his life.

With full access to the American consul’s massive library of Spanish history, Irving settled to work on the translation, then cast the project aside in favor of writing two projects of his own. In a remarkable feat of multi-tasking, Irving began working on both a history of Spain and a biography of Columbus. His work ethic impressed at least one young visitor to Madrid, Henry Wadsworth Longfellow, who loitered in town for months, watching Irving in awe. “He seemed always to be at work,” Longfellow said. The first offspring of this hard work, The Life and Voyages of Christopher Columbus, was published in January 1828 to critical and public acclaim in Spain and America. It was also the first project of Irving’s to be published with his own name, instead of a pseudonym, on the title page.

The work continued, and Irving took up residence in Seville to finish writing his Spanish history. The finished product, The Chronicle of the Conquest of Granada, went to press in April 1829 even as Irving worked on Voyages and Discoveries of the Companions of Columbus, a follow-up to his Columbus biography. Granada was more of a critical than commercial success, but Irving’s biggest gripe was with his English publisher, John Murray, who had placed Irving’s own name on the title page instead of publishing it under yet another pseudonym Irving had cooked up for its publication.

In 1829, Irving moved into Granada’s ancient palace Alhambra, dreamily strolling its halls and writing in his notebooks. He had only just settled in when a letter arrived informing him of his appointment as Secretary to the American Legation in London. Worried he would disappoint friends and family if he refused the position, Irving left Spain for England in July.

Arrving in London, Irving joined the staff of American Minister Louis McLane, who appreciated Irving’s considerable social skills and literary reputation as valuable tools for diplomacy. For the next year, McLane and Irving maintained a rigorous schedule, mixing both business and pleasure as they successfully negotiated a complicated agreement regulating American and British trade with the West Indies. When Irving found time to write, he made the most of it, completing Companions of Columbus by the end of 1830. He was also awarded a medal by the Royal Society of Literature in 1830 and an honorary doctorate of civil law from Oxford in 1831.

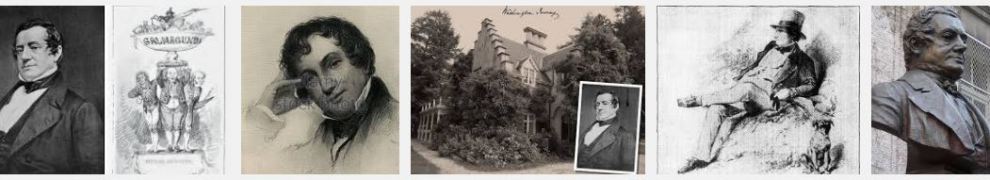

Washington Irving in the 1830s. (Etching based on a painting by Gilbert Stuart Newton.)

When McLane was recalled to the United States in 1831 to serve as Secretary of Treasury in the rapidly imploding Jackson cabinet, Irving stayed on as charge d’affaires until Martin Van Buren arrived in September. With Van Buren in place, Irving resigned to concentrate on writing, cranking out an embarrassingly incomplete Mahomet biography as well as a more polished piece, The Alhambra, based on his time in the Spanish castle. Presented with these manuscripts, publisher John Murray balked at Irving’s asking price. Angry, Irving vowed to never speak to Murray again (you can read excerpts from their fiery correspondence right here). Alhambra would be published a year later by a different publisher; Mahomet would be shelved for 20 years.

There was still more controversy. In 1832, the U.S. Senate, striking back at President Jackson, refused to confirm Van Buren as Minister to England. Irving sat up nights with his sulking fellow New Yorker, consoling him with the observation that this was a martyrdom that would propel him to the White House. “I should not be surprised,” Irving said, “if this vote of the Senate goes far toward elevating him to the presidential chair.”

Celebrity (1817-1825) | Professional (1826-1832) | American (1832-1842)