“Yes, I’ll Write To You…”

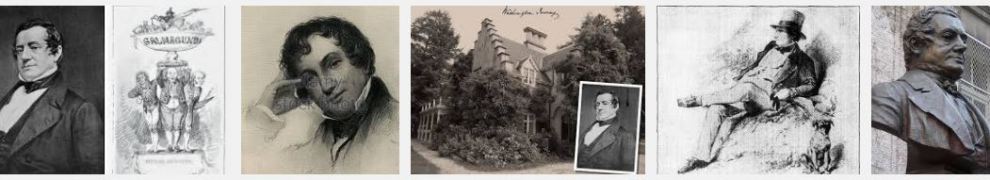

Irving’s English publisher, John Murray II, presided over an admirable stable of literary talent that included not only Irving, but Walter Scott, Lord Byron, and Jane Austen. Beginning in 1819 when Murray—at the request of Walter Scott—had rescued Irving’s Sketch Book from a bankrupt publisher, Irving and Murray enjoyed more than a decade of success together, producing one international bestseller after another.

In 1831, however, their relationship soured, due largely to bad timing and poor communication. As Murray struggled to remain afloat in a sagging book industry, Irving attempted to pawn off on his publisher two works in progress—one, an unfinished biography of the prophet Muhammad, the other, an embarrassingly incomplete Alhambra.

During a face-to-face meeting with Murray in London, Irving attempted to bluff his publisher into believing his two books were nearly finished—or, at least, could be completed quickly. Unimpressed, Murray asked his author to show him the manuscripts. If Irving believed Murray had called his bluff, he never blinked. He promised to send the manuscripts to Murray, as he was “anxious to get this matter settled.” Murray’s reply as he hustled Irving out the door was brief and noncommittal: “Yes, I’ll write to you.”

Oddly, Irving took Murray’s non-responsive response as a verbal agreement that he would publish both manuscripts—and Irving immediately dispatched his literary agent, Colonel Thomas Aspinwall, to take care of the paperwork.

As their correspondence in this section illustrates, the conversation went downhill from there…

Washington Irving to John Murray II,

Birmingham, October 4, 1831

My dear Sir,

In the hurry of leaving town I had not time to make a written agreement for the works about which we bargained. I have therefore requested my friend & agent Col. Aspinwall to call upon you and arrange in my name the terms of payment, and reduce the whole to writing . . . I will thank you to have the work put to press as soon as possible and furnish proof in slips, as I may wish to make occasional alteration & additions. . . .

This met with no response, so Irving tried again:

Washington Irving to John Murray II,

Sheffield, October 22, 1831

Dear Sir,

I wrote to you between two and three weeks since wishing the arrangement to be closed with my agent Col. Aspinwall about the publication of the two works which I have ready for the press and which for various urgent reasons I wish to have published immediately . . . I find however by a letter from him dated the 21st that he has not been able to see you on the business. As this delay is excessively annoying to me and impedes all my plans and movements, and as it is very probable that you may not be desirous of publishing at this moment, I am perfectly willing that what has passed between us on the subject should be considered as null and void. . . . I trust, therefore, you will not take it amiss if I seek some other person or mode to publish it. Nothing but the particular circumstances which hurry me at this time would make me quit my usual channel; but time is every thing with me just now.

The letter got the desired rise out of Murray, who was in no mood to be lectured:

Albemarle Street, [London,] October 25, 1831

My dear Sir,

My reply was ‘Yes, I’ll write to you,’ and the cause of my not having done so earlier, is one for which I am sure you will make allowances. You told me upon our former negociations, and you repeated it recently, that you would not suffer me to be a loser by any of your Works; and the state of matters in this respect, I am exceedingly unwilling because it is contrary to my nature to submit to you, and in doing so at length, you will I am sure do me the justice to believe that I have no other expectations than those which are founded upon your own good feelings. The publication of [Irving’s biography of Christopher Columbus] cost me . . . £5,700 and it has produced but £4,700 —[Irving’s book Conquest of Granada] cost £3,073 and its sale has produced by £1,830 , making my gross loss of £2,250 —I have thought it better to communicate with yourself direct, than through the medium of Mr. Aspinwall.

Let me have time to read the two new MSS—and then we shall not differ I think about terms.

Furious, Irving fired back at his publisher, accusing of him of trying to renege on a verbal agreement which, according to Murray, had never existed:

Washington Irving to John Murray II,

Barlborough Hall, Chesterfield, October 29, 1831

My dear Sir,

This letter also met with no response. Irving was through with Murray—he would eventually find other English publishers for Mahomet and The Alhambra.

The two would remain at odds until 1835, when Aspinwall approached Murray about publishing Irving’s “American book,” A Tour on the Prairies. “You may tell [Murray] for me,” Irving told Aspinwall, “that I am really delighted to renew my old connections with him, and that it will give me the sincerest pleasure to promote his interests in any way in my power.”