When I last left you — at least for the purposes of this particular narrative — I was in the lobby of the Roosevelt hotel, monitoring text messages from Barb and Madi as they made their way up from Maryland on the train. They were running only slightly behind schedule (as I said earlier, “on time” for the Northeast Regional seems to mean about ten minutes late), so I arrived in plenty of time to meet them, even after walking the mile or so to Penn Station. A short cab ride back to the hotel (when did New York cabs start taking debit cards? Brilliant) and we went into a bit of decompression mode until it was time to leave for the St. Nicholas Society Event at 6:30.

The dinner was being held at the Coffee House Club over on West 44th, only a block or so from the hotel, and an easy walk in the brisk February air. The Coffee House Club is considered a private New York club, but it’s got an irreverent, tongue-in-cheek outlook that I love. (Its Constitution consists of a half-dozen “commandments”: “No officers, no charge accounts, no liveries, no tips, no set speeches, no rules.”) It’s also a comfortably unassuming place, just two large rooms — one a reception area, the other a cozy dining hall.

Just inside the door, I met Jill Spiller, the Executive Director of the St. Nicholas Society, who worked hard over the past few months leading up to the evening to take good care of me. True to form, she escorted us into the reception room and put off to one side a nice gift from the St. Nicolas Society, a set of glasses etched with their logo. Very nice.

The reception was a very classy affair, yet also laid back — St. Nicholas members are genuinely interested in telling and listening to stories, and a well-told story will usually cause an eruption of laughter. And people had so many different interests that moving from one small circle to another was like entering a live encyclopedia. Over here, you could talk about astronauts and one man’s collection of space memorabilia. In this corner, it was about children’s songs. Over here, people chatted about medicine. I even found one gentleman who had in his private collection one of my Holy Grails of Washington Irving portraits: a photograph of a painting of Irving’s best friend, Henry Brevoort. I had scoured the planet looking for a portrait of Brevoort back when I was working on Irving and had no luck — and now here was someone who had one. It’s wonderful when things like that happen.

After an hour or so at the reception (the hosts had done a good job taking care of Madi, ensuring there was plenty of teen-friendly food and drink), we were gently herded into the main dining hall. The President of the St. Nicholas Society, Dr. Billick — who is class and charm personified — had gone to great lengths to seat Madi on his left, with me on his right, and Barb right across from us at the horseshoe of tables. I smiled as Dr. Billick made certain to engage Madi in conversation throughout the meal, offering up history questions, chatting about the European Union (!) and generally making her feel at ease as the only young person in the room. Not that Madi can’t hold her own in almost any conversation (at one point, someone came up to me, laughing, and said, “After talking with your daughter, I asked her what she was majoring in. She told me ‘eighth grade’!”), but it was a lovely gesture on his part, and I so appreciated his effort.

We were still enjoying our dinners when it was time to conduct some business. Two new members of the St. Nicholas Society were introduced and initiated to much applause. I was then introduced by longtime member (and fellow New Mexican!) Mr. Hilliard, with Dr. Billick at his side, who stepped to the mike and presented me with their award.

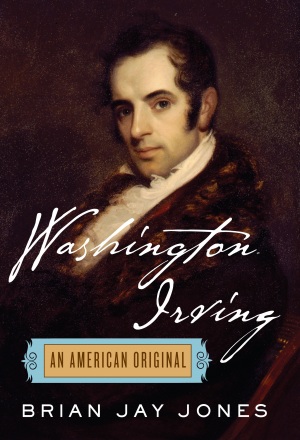

I promised everyone who wrote to me with their good wishes that I would put up a picture of the medal. Here it is — and it’s a beauty:

I spoke for about twenty minutes, telling one of my all-time favorite Irving stories: the hoax that Irving pulled off to launch his mock history of New York City, and the Dutch reaction to it (someone threatened to horsewhip him). Given the St. Nicholas Society’s mission to preserve and perpetuate New York’s history, I thought such a talk would be appropriate — and I was delighted that it went over so well. I took questions for about twenty more minutes, then spent the rest of the evening signing books, talking with members, and generally having a terrific time. It was one of the nicest evenings I’ve ever had — and having Barb and Madi there with me to share in it made it that much more special.

It was cold as we stepped out onto 44th for the walk back to our hotel — we had already changed our travel plans to leave early the next morning, in hopes of getting back to Maryland in front of the advancing snowstorm — but we walked slowly, trying to make the evening last even longer. Our thanks to the St. Nicholas Society for such a remarkable night.